Stanley Yelnats is unlucky. Most millennials and quite a good chunk of Generation Z are well aware of this truth, and that this bad luck can be blamed on Stanley’s no-good-dirty-rotten-pig-stealing-great-great-grandfather. Kids in 2023 are also learning of Stanley’s bad luck, as it took me a few weeks on my library’s waitlist to get a hold of Louis Sachar’s beloved children’s classic: Holes. Over two decades after its initial release, the book is still a hot commodity, though it has had its share of controversy. From a Google search, one can find that parents raised concerns about this book and got it banned from classrooms as early as 2009, citing the book’s violence as inappropriate for children. Today, when book banning in classrooms has become commonplace and a media firestorm, Holes, as beloved as it is,stands as an early example of this practice.

The books being banned today are an eclectic bunch. The reasons for banning them vary, from sexual content to language to violence. There has been understandable backlash to any book banning, especially in cases where books dealing with race, particularly books about African American experiences, have been banned. The most recent high-profile example of this being when a South Carolina high school teacher was told to stop using Ta-Nehisi Coates’s book on growing up Black in America in her class when students reached out to the school board stating that they were made to feel “uncomfortable” and “ashamed to be Caucasian.” Some parents called for the teacher to be fired. While it is reasonable that parents should have some involvement in what their children read, the government allowing the banning of books written by Black authors or anything that may make them “uncomfortable” has emboldened community members to attack any teacher or author that dares to suggest the United States is a racist country or suffers from systemic racism.

Holes, while written by a white author, is a book about systemic racism and how children suffer within the prison industrial complex. I first read this book in the third grade of my conservative Catholic school in Florida. I wonder if it is still on the reading list. Given the prevalence of book banning, and Holes being an early banned book at certain schools before it became a hot topic, I wanted to return to a childhood favorite of mine and many others. After re-reading it for the first time in many years, as well as giving the movie (the screenplay of which was also written by Sachar) a re-watch, I can confirm the story deserves its place as a classic of children’s literature. The book and movie deftly discuss in a way children can easily understand many important and difficult topics, such as how private prisons seek to enrich themselves under the guise of rehabilitating prisoners.

While the Texas based Camp Green Lake, where children dig holes for their supposed rehabilitation, is a fantastical setting, it is perfect for a complex message directed at a young audience. The campers are not digging to “build character” as Mr. Sir claims. They’re digging for treasure that will be handed to the Warden, the owner of the dried-up lake. The Warden inherited the land from her grandfather, a man who had once led a lynch mob and shot a Black man in cold blood. This book is a critique of prison labor, private prisons, and systemic racism, but where I have always found it to be the most radical is in its portrayal of the boys at this work camp, and the empathy it allows them.

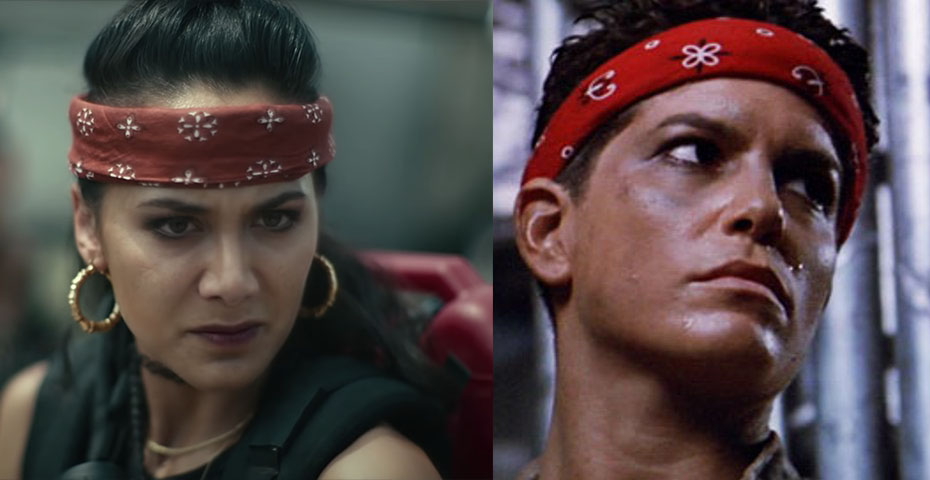

Stanley is our point of view character throughout the story. He is a lead most readers can connect with, especially at a young age. He is shy and awkward and struggles to make friends. He is also a fat kid, which the movie unfortunately changed when they cast the thin Shia LaBeouf in the role. Sachar implies that Stanley is Jewish, though it is mostly ambiguous. Sachar, who is Jewish, named Stanley’s pig-stealing-great-great-grandfather Elya, which is Sachar’s Hebrew name. The movie makes the Yelnats Jewish identity more explicit. Director Andrew Davis is himself Jewish and stated that he “detected a Jewish family” when he read the book, believing that the Yelnats immigration experience and struggle in America reflected that of the Jewish experience. Davis made the book’s Jewish implications explicit in his movie by casting Jewish actors Henry Winkler and Nathan Davis to play Stanley’s quite delightful father and grandfather, respectively. A sharp listener will notice Davis’s grandfather character, who was invented for the movie, make remarks in Yiddish. LaBeouf also comes from a Jewish family.

Sachar allows the reader to feel pity for Stanley and frustration with an unfair justice system from the first few pages when it is revealed that Stanley was arrested and convicted for a crime he did not commit. He was simply unlucky, in the wrong place at the wrong time. This, of course, is nothing unique within the American justice system, particularly for impoverished people like Stanley, whose family cannot afford a lawyer, and even more so for Black and Brown Americans. Stanley begins the story rightfully frustrated that he has been sent to a labor camp by the state when he did nothing wrong, blaming his great-great grandfather for his bad luck. Stanley is justified in his anger, and the story never reprimands him for his feelings. His journey throughout the story, as the director also put it, is one of learning to understand his own family struggle and how this helps him empathize with other people who are struggling.

At Camp Green Lake, Stanley is faced with other boys who face great obstacles and bad luck of their own. The crimes they may have committed which I discuss here are not ever disclosed in Holes (save for Zero) but were either revealed in Sachar’s sequel, Small Steps, in the movie, or otherwise revealed and put the Holes wiki pages. We have X-Ray, the leader of D-tent. He is a Black boy who one presumes has been at Camp Green Lake the longest of the boys and enjoys his position as the top of the food chain. X-Ray comes across as the smartest of the group, often rattling off random facts to correct the other boys. Given his brains, it seems fitting that he was arrested for running a scam: selling bags of dried parsley to people who believed they were buying marijuana. Personally, X-Ray is my favorite, and I appreciate that the movie was a bit more sympathetic to him. Next comes Armpit, who may have been Sachar’s favorite given he is the main character of Small Steps. He is another Black camper, the funny guy of the group, and reads as X-Ray’s second in command, perhaps because he has been at the camp the second longest amount of time. Armpit was arrested for fighting two other boys over a bucket of popcorn at a movie theater.

Squid is one of the more rambunctious boys in D-tent. He is a white boy with a smart mouth who seems to resent Stanley’s positive relationship with his parents. While the book does not allow for too much insight into Squid, there is a notable scene when Stanley wakes up to hear Squid crying. In the movie, Squid states that his father is absent and his mother is an alcoholic. Squid was arrested for fighting a police officer. The D-tent member who Stanley clashes with the most is Zigzag, a zany white boy who the movie indicates suffers from mental health problems. While Zigzag was arrested for setting off firecrackers at school, he seems to be more prone to violence than others as he picks a fight with Stanley. Next is Magnet, who always came across in the movie as the sweetest member of the group, and the one who struggles the most with his place toward the bottom of the pecking order. Magnet is Hispanic, perhaps Mexican, and was arrested for stealing a puppy from a pet store. Finally, we have Zero, who is the co-protagonist of our story. Zero is a Black boy who faces perhaps the greatest obstacles at Camp Green Lake, as nobody respects him. He is the target of frequent harassment by their counselor Pendanski, and the other boys bully him, even putting Stanley ahead of him in the line to get water despite Zero having been at camp longer. This, it is implied, is because Zero refuses to speak or otherwise interact with anyone at the camp, leading people to believe he is stupid and earning him the nickname “Zero.” His silence, we learn, is due to his dislike of answering questions and is his way of refusing to cooperate, particularly with Pendanski, who is most put off by Zero’s muteness.

These boys are not angels. It is apparent that they made mistakes that landed them at Camp Green Lake, though these mistakes hardly warranted months of hard labor in the desert. Further, Sachar allows for the arrests of all the boys, even though we know very little about what happened, to remain suspect. As Stanley was convicted of a crime he did not commit and could not afford a lawyer. Zero was arrested for stealing shoes when he needed them while homeless. Still, the boys are not particularly kind. They bully Zero, and Zigzag could have done great harm to Stanley when they fought. Though it is important to note that their behavior worsens out of understandable frustration when Stanley receives help from Zero in digging his hole while the rest of them work alone. Despite their behavior, the book never paints them as the villains of the story, but victims alongside Stanley and Zero. Is it any wonder they are not the kindest of people when they perform backbreaking labor with little water in the hot sun under armed guard every day? They are also physically abused by the authority figures. The Warden at one point draws blood from Armpit with a rake. Squid is thrown to the floor by Mr. Sir for daring to ask how he got scratches on his face. These boys are allowed little help for their rehabilitation and instead are regularly faced with insults, violence, or threats of violence from those who are supposedly turning them into “good boys.” Even Stanley, Sachar states in the book, becomes hardened by his experience at Camp Green Lake. He loses some of his goodness.

Camp Green Lake is an imaginary setting, but the abuse faced by the campers reflects the experience in real life juvenile detention facilities. Almost half of youth containment facilities in the United States are privately owned. Research suggests that for-profit prisons are associated with increased violence towards prisoners. Abusive practices in the prisons include beating handcuffed youth, unsanitary food, regular sexual assault, etc. Another example being guard-instigated fights between prisoners. Zigzag and Stanley’s fight in Holes appears inspired by these incidents. As when Pendanski, who I’ve always read as the most nefarious of the Camp Green Lake authority figures despite his “nice guy” demeanor, sees Zigzag trying to provoke Stanley into fighting him. Instead of stopping it, Pendanski encourages it, telling Stanley to hit Zigzag back. Here they are at a camp that is supposed to “build the character” of juvenile delinquents, and their counselors are egging them on to hit each other for a power trip. Rehabilitation is not possible here. They only seek to further break these boys down in an abusive environment. Why wouldn’t they? Their presence in detention facilities is profitable.

The D-tent boys and the rest of the campers aren’t angels, it’s true, but that as Sachar always makes clear, that does not make the abuse they suffer justifiable. This is one of the most potent themes in the book. Criminals, adults and children alike, are often brushed off by society as deserving of whatever punishment they get. You break the law, you deserve punishment. It is this mindset, this detestation of perceived “criminals” that allows for an abusive system to thrive. In a world that sees the suffering of people out of prison, very little interest can be spared for the wellbeing of those that commit crimes and get locked up. Holes challenges us to rethink this indifference, to see the suffering of those who are essentially owned and live at the mercy of an abusive system.

This is a book full of convicted criminals that we are asked to empathize with, which is unique in children’s literature. We have the campers, but we also have Katherine Barlow, or Kissin’ Kate Barlow. Kate is certainly a more hardened criminal than any of the boys, not to mention she is an adult. She was a thief and a murderer for twenty years. As is the case with the Camp Green Lake boys, Sachar asks us to empathize with Kate by showing us why she became a murderer. Her lover Sam, a Black man, was murdered by Trout Walker, who owned the town and the lake. After witnessing this, she shoots the sheriff, who allowed Sam’s murder to happen. She then spends the rest of her life robbing people, banks, and committing murder. We are not privy to every person she killed, but it appears from the movie that it was predominantly white men. While her desire for vengeance against the powerful is understandable, she clearly also murdered those who did not deserve it. The first Stanley Yelnats was left stranded in the desert after she murdered his entire escort for his money. This, to be sure, cannot be justified, but Sachar doesn’t try to justify it. He just seeks for the reader to understand how she became this way. The rage that triggered her turning to a life of crime was directed at a system that allowed Sam to be murdered without consequence. Over a hundred years later, on that same lake, the descendent of Trout Walker was still able to abuse the marginalized. This is why the curse on the land prevails even after his death. It is notable that Sachar states that “God” punished Trout Walker and his land for what he did to Sam, but never suggests that God punished Kate for her violence.

Like Kissin’ Kate Barlow, the campers of Green Lake adopt nicknames and refuse to go by the names “society will recognize them by” perhaps in part as a rejection of a society that has rejected them. The boys of Camp Green Lake are a rough crowd, but they still look out for each other better than any authority at the camp. When Stanley almost stumbles into a fight with another camper at the beginning of the story, it is his fellow D-tent campers who defend him. When Zero chokes Zigzag in the fight that Pendanski instigated, it is Armpit that pulls Zero off him. Stanley and Zero’s relationship is the heart of the story, and they take care of each other more than anyone else. One issue I had with the book on this re-read was I would have liked to see more comradery between Stanley and the rest of D-tent, as he is a lot more solitary than I remembered until he finds friendship with Zero. Perhaps Sachar judged this to be a flaw in his book, or it’s a Hollywood revision, as the movie shows far more warmth among the members of D-tent. A more cliché Hollywood choice, sure, but I must say I prefer it. It allows us to better connect with all the campers.

It is in Stanley’s relationship with Zero where we can best see what the director of the movie, and Sachar as well, intended to be Stanley’s arc of empathizing with those around him. Stanley and Zero become friends, and through this friendship Stanley learns just how difficult Zero’s life has been. Zero was without his parents, homeless, and illiterate, along with being Camp Green Lake’s favorite punching bag. Throughout the book, the reader comes to realize that Zero, who is revealed as Hector Zeroni, is the descendant of Madame Zeroni, the Egyptian woman who placed the curse on the Yelnats family for Elya Yelnats’s failure to uphold his end of their agreement.

Over a hundred years later, another Yelnats and Zeroni find each other in Stanley and Hector. Perhaps the greatest irony of the book is that Hector, the descendant of the woman who cursed Stanley’s family, has a far more difficult life than Stanley. This is shown most starkly when Stanley and Hector realize they both frequented the same park in their hometown. Stanley used to play there. Hector used to sleep there. Upon hearing this, Stanley is shocked and saddened. Stanley’s struggles are never mitigated by the book or movie, but he comes to recognize his own privileges when exposed to the struggles of other campers, primarily Hector. Stanley has two parents that support him. He has a home. He has an education. He is white. Sachar is able to walk a careful line where the story never tells Stanley “Check your privilege and be happy” as he clearly faces his own struggles in a corrupt system. Holes is never telling us that we should just be grateful for what we have because it could be worse. Rather, it encourages us to understand our own struggle as well as the struggles our parents and ancestors faced, and through this we can better empathize with the people around us, who are facing their own battles, some greater than we can imagine.

When Stanley and Hector depart Camp Green Lake at the end of the story, Armpit (or in the movie, X-Ray) tells Stanley “You be careful out in the real world. Not everybody is as nice as us.” This reads as an acknowledgment of the kinship these boys shared at Camp Green Lake. It was far from a utopia, as they were living under an abusive authority, and the campers themselves were hardened against each other by this abuse. Still, they suffered through this together in a way that no one in the “real world” would understand. In the real world they were convicted criminals. Among each other, they were fellow kids who were dealt a bad hand and landed themselves in the middle of the desert to dig holes every day. We leave Camp Green Lake knowing that there was a brotherhood there, an understanding among boys who were cast out by society to suffer hard labor and abuse. The real world is cruel to these boys, making them into numbers with shovels rather than flesh and blood. Stanley can see this by the end of the story, sees their struggles and their humanity. Sachar dares to ask us, and the children who read or watch his story, to do the same.